History of Mirfield

In the dim and distant past Mirfield must have been covered by dense forests. These forests were compacted over many thousands of years and were converted to coal which gave rise to the mining industry that flourished in and around Mirfield through the 19th and the first half of the 20th centuries.

A written record of the existence of Mirfield appears in the Doomsday Book of 1086, which was a complete survey of the whole country ordered by William the Conqueror after his successful invasion of England in 1066. The word MIRFIELD is thought to mean a clearing near a swamp or mire. This had been incorporated into the Mirfield Coat of Arms in the motto - 'Fruges ecce paludis' - which translates to - 'Behold the fruits of the marsh'. However in Pobjoy's 'A History or Mirfield', he puts forward an alternative theory in that the prefix is from the Old English 'maer', meaning merry or pleasant. Choose which explanation you like.

Following the Norman Conquest, Mirfield and Hopton were among 214 manors, mainly in Yorkshire, that were given to Ilbert de Lacy who had been responsible for much devastation in the subjugation of those who resisted William's occupation. Ilbert is thought to have fortified his manor at Mirfield with a motte and bailey, using the mound and moat already in existence from earlier fortifications. This mound still stands beside the Parish church.

Past and Present Places of Interest in Mirfield

The Tithe Barn

The Tithe Barn was situated in the grounds of Blake Hall at the Pinfold Lane entrance near the Old Rectory. In days of old it was the place where tithes due to the Rectory were collected in kind.

Exterior

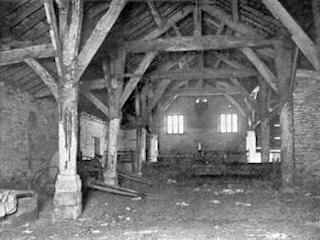

Interior

In Reverend Hall's 'A Short History of

The Parish Church of Mirfield' published in 1947, he states:

"The building is still in a good state of preservation. We may be proud that this link between the past

and the present is still preserved to us."

If only this was still true as the barn was demolished soon after this was written.

Here is an interesting extract from The Reporter of June 21, 1952:

The thirteenth-century-old barn on the estate has recently been demolished, as damage caused to it by vandalism had made it unsafe.

Mr. Maurice Avison of Parker Lane, owner of the estate said the damage to the tithe barn had been going on for a long time.

"The culprits knocked down a wall inside the barn," he said. "They have broken every window in there, and dropped a heavy oak beam to the floor." The damage to the barn cost over £100, and would have cost over another £200 to repair. It was therefore demolished.

Fruit and flowering trees in the estate gardens have also been stripped, and damage to a new building close to the old tithe barn has amounted to over £20. The building, formerly a piggery, has had all of its windows broken.

The Stocks and Ducking Stool

The Stocks

Stocks in England have a long history and must have been an effective deterrent to petty crime. Perhaps there are lessons to be learned even today. Stocks had to be provided in each parish as far back as the mid 14th century and miscreants were locked into them for several hours at a time. The local youngsters would be free to pelt the unfortunates with rotten vegetables while others would taunt them at will. The remains of the stocks are still to be seen outside Mirfield Parish Church in Church Lane.

The ducking stool was situated at the bottom of Pinfold Lane across from the Old Rectory where there used to be a pond. Ismay records that it was used for the correction of scolds and other unquiet women to the delight of people watching. Bakers of substandard bread, brewers of bad ale, and publicans who gave short measure could also qualify for a ducking. The Towngate sump was situated at Pinfold so a good supply of 'impure' water was assured.

The Sluice

When I lived at Pinfold Lane there was a trap door set in the north-eastern corner of the field, which we called our garden that gave access to an underground culvert by means of iron rungs set into the wall of a shaft. At a very early age we would don our Wellington boots and clutching a small torch would climb down the rungs and paddle in the water through the circular pipe to emerge some 200 yards further along at the sluice shown in the photo on the right. Where the decorative bridge is now, was a sluice gate that regulated the flow of water for a market gardener situated next to Blake Hall. One day we walked through to find that the end of the pipe had been blocked by a metal grille so that was the end of our adventures.

When I returned to lived at Towngate in the 1960s, after a particularly heavy rainfall, the Grammar School back-field would become waterlogged and water would pour over the retaining wall and rush along Towngate to a depth of several inches. It would come through our gate, thankfully bypassing the house and rush down a gully at the side of the house next door then into a drain in their garden which finally led to the sluice at Pinfold. I was reminded of this on 15th June 2001 after a cloud burst. We were returning home from Mirfield via Towngate when we witnessed the very same thing with a few inches of flood water running along Towngate from a veritable waterfall cascading over the wall near the bottom of Sous Lane.

Dumb Steeple

Dumb Steeple

During the 40s and 50s Dumb Steeple stood in the centre of the grassy roundabout at the road junction at Cooper Bridge. Later, when the road layout was changed, it was moved to the side of the road where it stands today.

It has featured quiet heavily as a rallying point for insurrectionists during the past history of Mirfield. During the Luddite rising in the early 19th century, when the textile workers, fearful for their jobs, set about systematically raiding mills and trying to smash the new looms which were being introduced. It was Dumb Steeple from where the ill-fated raiders started out in 1812, across the fields to Rawfolds, near Cleckheaton, to attack Cartwright's mill.

Although most of the Luddites came from the Huddersfield and Halifax areas, there is evidence that a few sympathisers from Mirfield had joined in. Cartwright, the resourceful mill owner, had been warned that something was afoot and had secretly introduced sharp-shooting yeomanry into his building. When the Luddites rushed into the mill yard, they were picked off by the troops in the upper floors.

One or two were killed and many were wounded and taken prisoner. A few months later several were hanged at York in the presence of more than 30,000 people though there is no record that any Mirfield men were among those who stood trial at the Assizes.

In 1819 a large group of men stirred up by a Dewsbury agitator named Henry Hunt and armed with whatever weapons they could muster gathered at Dumb Steeple to march on Huddersfield. They had gathered for many months at Westfields and Tanhouse where they were put through arms drill by others who had served in the wars across the Channel. They marched on the evening of March 31st which was Good Friday but it appears that some of the Mirfield contingent either devleoped cold-feet or failed to overcome their wives' suspicions.

Whatever the reason, the "rising" developed a farcical aspect. The leaders at Dumb Steeple angrily sent lieutenants to round up those missing from the Mirfield contingent but most of them were not at home. In fact, they had taken to the fields and the woods. It is recorded that many climbed the trees and found concealment in the large rookery near Blake Hall. Though on this occasion they showed no gallantry, they displayed a degree of discretion and anticipation which perhaps did them even more credit because the attack was easily repulsed by the yeomanry and hussars and came to nought.

click to read inscriptions

Kirkheaton Memorial

The actual origins and purpose of Dumb Steeple are mostly shrouded in mystery and folklore. It is thought by some to have been a landmark to guide travellers on their way across the moorland, and standing as it does at Cooper Bridge on the junction of the routes to Huddersfield, Brighouse, Leeds and Mirfield this adds some credence to the theory. It has also locally been reputed to have been built as a memorial to several children burnt to death in a mill at Colne Bridge. The tragedy happened on the night of 14 February 1818. A foreman, going out, presumably for a drink, locked in seventeen girls. A fire broke out in his absence, and all of the girls were burnt to death. Three were nine years old, and all except three were under fourteen. They were buried together in Kirkheaton churchyard where their memorial, pictured on the right, can still be seen. However, if we accept that the Luddites met at Dumb Steeple in 1812 then this must disprove this idea as the steeple then predates the tragedy.

Getting nearer to our own time, in June 1927, there was a political gathering of another kind at Dumb Steeple. Workers laid a wreath at its base as a silent protest against the Trades Dispute Bill which was then before Parliament. The Steeple has seen many stirring events, though how it came by its name is indeed a mystery.

The Temple

The Temple

Although not strictly within the boundaries of Mirfield, the Temple has been a part of the Mirfield skyline since it was built in the grounds of Whitley Hall. There is some mystery as to the actual purpose of the structure but it is generally believed to have been used as a summer house. It stood at the end of the Terrace Walk, overlooking the entrance to the drive leading from Liley Lane to the Hall which was known for its beautiful displays of rhododendra. It has been known locally as Black Dick's Tower, but was however built some time after his death. Black Dick was Sir Richard Beaumont and the nickname 'Black Dick of the North' was given to him by James I. He was born in 1574 and died in 1631. A splendid tomb was erected for him in the Beaumont Chapel of Kirkheaton church.

When we played around the tower in the 1950s there was a stone floor with a basement underneath but the floor has now all gone leaving a drop straight into the foundations. The original Hall was built in 1560 and was added to in 1704 when the two wings were joined by a new front enclosing the area between to form a quadrangle inside. It had been home to the Beaumont family for most of the time but the last owner was Mr. Charles E. Sutcliffe who bought the Hall and estate in 1924. It was sold for demolition in 1950 but the Temple was allowed to remain. Following the demolition, the land was excavated for open cast mining and then was landscaped when the mining finished.

The History of Mirfield

It has often been conceded by antiquaries that Mirfield boasts a local history more interesting than that of most towns of its size in the West Riding. Certainly, from its first appearance in the early written record of organised life in these islands, as an entry in the Domesday Book ("Mirefelt: Six carucates of land, each as much as two oxen can plough in a year"), it has caught quite a few of the facets of the English tale through the ages.

Until 1261, Mirfield had no parish church - only a chapelry because in Saxon days Dewsbury was the centre of the far-flung parish of no less than 400 square miles. Then a dispensation was granted and the first church was built in Mirfield. Its tower still stands beside the present fine parish church, designed by Sir Gilbert Scott himself, made and consecrated in 1871. It cost £22,000. Sir Gilbert made suggestions for the preservation of the tower of the old church after the nave and chancel had been pulled down, providing, incidentally, part of the stone from which the former Eastthorpe School, now Eastthorpe Visual Arts, was built.

The 14th century found Mirfield a flourishing centre of the woollen industry and already a place of some agricultural and industrial importance. In 1378, the Poll Tax in Mirfield was 59 shillings, which, it need hardly be stressed, represented a sum out of all proportion to today's money values! Huddersfield produced 19 shillings and fourpence and Halifax 12 shillings and eightpence. Many important families settled in Mirfield, the Hoptons, Saviles, Thornhills and Beaumonts among them, and the remains of some of the fine halls they built may still be seen. At Battyeford, near Warren House, were the butts where local men mastered the art of the longbow. During the Middle Ages, and later when the Civil War swept the country, the district seems to have raised its quota when military needs had to be met. One of the few relics of defence surviving in the district appears to be the mound near St. Mary's Parish church graveyard. Pontefract, a mediaeval historian, describes it as "a moat and baily castle made by Ilbert de Lacey (who owned Hopton Hall) as a minor stronghold to support his possession of manors, "The church was built in the courtyard of the castle."

In January 1642, the Civil War came near to the locality when Sir Thomas Fairfax wrote to the Constable of Mirfield ordering "all that be of able bodyes from the age of 16 to 60 to repair to Almondbury on Saturday with all weapons they can procure and provisions for five days" to assist "in driving out the Papist army," The Constable was warned "to fail not at your peril". The Pretender Charles threw his shadow across the neighbourhood, too, with more spectacular results. When he and his army were marching to Derby in 1745, he produced something like mass-panic in Mirfield. Fearful that the Scots were going to sack the town, men and women hurried with personal belongings and food which they hid in local coal workings.

The Rev. Joseph Ismay, Vicar of Mirfield from 1735 to 1778, who kept a most informative diary, or journal, recorded that "on the Sunday, few women attended the service for want of apparel". To Ismay, indeed, we own much for a picture of Mirfield as it apeared two centuries ago. He reminds us, for instance, that in 1755, with a population of 2,175, the district had 100 pairs of looms for weaving broadcloth, worked by 200 people, with 400 others engaged in carding, spinning, and other kindred occupations - many of these doubtless the ancestors of the people who today are engaged in the town's woollen industry. There were 40 pairs of looms in Hopton, where, says Ismay, "the men and boys employed themselves in the Christmas holidays in hunting the squirrel which gives them violent exercise in the woods and affords them excellent diversion".

The River Calder yielded, in Ismay's time, "salmon, trout, smelts, graylings, dace, perch, eels, chub, parbles, and gudgeon, and about it are found wild duck, widgeon, tea, coots and several sorts of water hens, especially in great frosts". There was a great frost too, in 1772 when the diary relates: "The country was seized with so great a freezing that people did skate on the Calder all its length from Mirfield to Brigg House and carts and horses did pass freely across without danger thereto." London had its Great Plague in 1665, but a similar scourge had taken a deadly toll in Mirfield 34 years earlier. Workmen digging for foundations for a new house at Snake Hill uncovered a pit almost filled with human bones - without doubt those of some 130 men, women and children who died when a pestilence struck the town in 1631. A woman was thought to have brought the infection from the south of England and records tell us, "pits were dug at Littlemoor and Eastthorpe Lane wherein were interred a vast numbers of bodies. Some were put to rest in the churchyard, but many did bury their dead near their houses". A stone memorial, formerly in the old church and now preserved in the Parish church, records the plague with which, it declares "it pleased God to correct ye Parish of Mirfield".

That the Mirfield people, like the rest of the human kind, were deemed in the old days to stand in need of correction from time to time, is shown by the fact that, until last century, the town stocks were in use near the Parish Church - the stone uprights today support a wooden seat. Nearby, across the road from the well preserved half-timbered Old Rectory, was the ducking stool which, in Ismay's day "at uncertain and necessarily irregular intervals is used for the correction of scalds, viragoes and similar unquiet women, likewise bakers of sour bread, to the delectations of persons watching the punishment". A 1657 entry in the Quarter Sessions record recalls that two men were convicted "of drinking and tippleing upon the Sabbath at ye house of an alehousekeeper for which offences they have forfeit 10 pence or else to sitt in ye stocks six hours". We have the testimony of no less a reliable authority than John Wesley to the fact that Mirfield had its share of tough customers 200 years ago. He visited the locality five times between 1742 and 1784, often staying with his great friend Benjamin Ingham, of Blake Hall. After one such visit to Huddersfield and District, this entry appears in the Wesley diary: "A wilder people I never saw in England... they were, however, tolerably quiet while we preached and only a few pieces of dirt were thrown."

Nevertheless, John contrived to open Mirfield's first Methodist Church at Knowl in 1780. And that there were other God-fearing folk in the area then is graphically proved by the fact that Tamar Lee, wife of an ardent Hopton Congregationalist, rode the thief-infested roads to London on horseback in 1732 with an appeal for funds for the building of her denomination's first church. She returned with £52 8s 6d. In 1816, too, the first Baptist meetings were held in Mirfield, in the old Tythe Barn in Towngate, and the first Baptist Church was opened in 1830. The Moravians built their first church in the town in 1751. Christ Church was consecrated in 1839, (destroyed by fire in 1971), St. John's (Hopton) in 1846, St. Peter's (Knowl) in 1874, and St. Paul's Eastthorpe) in 1881. While today, Mirfield is known throughout the Anglican world as the home of the Community of the Resurrection, with its neighbouring training college. Those two illustrious co-founders of the Community, Bishop Gore and Bishop Frere, have their last resting places in the Community precincts at Mirfield.

Educationally, Mirfield comes into the picture in 1667 when Richard Thorpe, a local parson of independent means, endowed a free school "for teaching fifteen poor children of the inhabitants of the parish till they can read English well". This foundation later became Mirfield Grammar School (now The Mirfield Free Grammar). A baker's boy at Wellhouse Moravian Board School towards the end of the 18th century, was passionately fond of poetry. His name was James Montgomery. With 3s 6d in his pocket he ran away to Wath in South Yorkshire, later settling down in Sheffield after a sojourn in London. He became one of our greatest hymn-writers, his works including Hail to the Lord's Anointed, Angels from the Realms of Glory and Prayer is the Soul's Sincere Desire. Years later, a student from the same school became Prime Minister - the first Earl of Oxford and Asquith.

Roe Head, once a school for refined young ladies, a former training college and now home to Holly Bank School for youngsters with physical and learning difficulties, had strong connections with the Brontes. In 1831 Charlotte Bronte of Haworth arrived and later became a teacher there, her sisters Emily and Anne were among pupils there. Anne was later employed as a governess at Blake Hall by the Ingham family. Background and "atmosphere" gained during their stay in Mirfield found their way, very naturally into a number of the three sisters' famous writings.

Mirfield not only shared in the benefits of the Industrial Revolution but also in the disorders which its early stages brought, at a time when local textile workers feared that the new power looms must inevitably mean unemployment and misery for themselves and their families. There seems little doubt that Mirfield men were among the Luddites who gathered near the Three Nuns Inn, not far from Robin Hood's reputed burial place in Kirklees Park, one night in 1812. They marched across the fields and attacked Rawfolds Mill in Cleckheaton where the new looms had been installed. The military had been warned, the raid failed and numbers of Luddites were hanged at York. Inevitably, however, the machine age developed - and so did Mirfield, not only industrially, but also as a communications centre. It had been served by the canal since 1766 and the railway which reached the town in 1848 eventually brought additional employment as well as advancing commercial prosperity.