Journal of Philip Highe

A true story seen through one pair of eyes, from soon after the first war, right up to the affluent 1980s

The Beginning

The first thing I can remember was when father, Charlie, sat my sister Phyllis and me on the horsehair sofa when I was nearly four years old and Phyllis only two, in our living room at 7 Northorpe Lane, and told us that we had a new little brother. This little brother we named John David, but for some reason he's always been called Jack. As we got a little older, Phyllis and I used to be always doing battle with each other and it wasn't until the war started in 1939 that we sorted ourselves out. The house later became known as "Ye Olde Toffee Shoppe" and is now demolished to make way for road widening. When, at the age of five, I started school, it was at St Luke's Infants School in Northorpe Lane. The school, which belonged to St Mary's Parish, had three classrooms and little else. The privy was down at the bottom of the sloping playground and was smelly and not too clean. Mother told us not to use it, instead we were to go home and use ours.

At this time washing was done by the use of a peggytub and posser, then later on a device called a washing machine, which was another tub, fitted with a sort of gate with handles. This had to be worked backwards and forwards by hand, forcing the water through the clothes. These were then passed through large wooden rollers to squeeze the water out. On fine days the clothes were pegged out on a line in the garden to dry. When it was wet they were hung over the clothes horse in front of the fire. Our relatives, who lived, in the Flatts area of Dewsbury, a tough working class district, had to hang their washing at first floor level to allow the traffic to pass underneath.

My father in uniform

Father, Charles Edmund, and Mother, Bessie, met in London in 1916 during the First World War, he was in the R.A.S.C. and she in service and they married on Guy Fawkes' day in l917. After returning to France he was wounded when his horse was shot from under him and ended up with a bad leg with which he suffered all his adult life and for which he had a (small) Army pension. I was born in Greenwich Village, London on 26 Jan 1919, so I should have been a Cockney. Instead I was brought to Yorkshire when Pa was offered a job as a baker by his sister's husband, Uncle Tom. I remember the lovely smells that used to come out of that bake house. The same housing problem faced them then as it later did us after the Second World War. So, having nowhere to live, they were forced to live-in with his father (also Charles) and mother in a tiny two up and one down house in Arthur St, in the Flatts area of Dewsbury. Mother told us later that old lady made her life hell. I could imagine it too when I visited as I got older. It must have been difficult with the privy at the end of the street but that was usual in those days.

School Days

I must have been about 11 when I was sent to Crowlees School and experienced teaching by some really dedicated people. Crowlees was a boys' school and also belonged to the St Mary's Parish. Headmaster and teacher was Willie Benn, senior teacher was J.U. Pyrah, junior teacher Miss Katie Butt. Some of our crowd were fortunate enough to move to the Grammar School next door (Now Castle Hill School). For some reason which I could never understand, I was never offered a place, or even an entrance exam. Nevertheless it has not made a lot of difference in the end. Perhaps I wasn't bright enough, but I was one of the boys selected by Mr Pyrah to give what he called "Littleman Lectures". On Friday afternoons, after playtime, one of the lads would talk to the rest of the class on his favourite subject. Mine was always something electrical. After one talk about how telephones worked, Mr Pyrah said "This boy is a disciple of Michael Faraday" and for months afterwards I was being called nicknames like Disciple, Faraday, or some names that were ruder. Lads can be cruel.

Nerecar

Father was mechanically minded, he used to acquire broken down motor cycles and set to work making them run again. We often got to ride as passengers on them and I remember one in particular, a Neracar. This was really a scooter, long before its time. One of us would ride on the back and the other on the engine, something that wouldn't be allowed these days. Eventually we got a second hand Morris 8, followed by a Ford, dad could drive anything on wheels also on hooves (horses). The cars were a lot better than motor bikes as we, by now five, children could all squash in.

Bath nights were on Fridays, we used to take turns in the big tin bath in front of a roaring coal fire, screened by a blanket on the clothes horse. This gave a bit of privacy, something you don't get a lot of in a mixed family. My bath nights came to end, when Jack and I started going to the swimming bath at Heckmondwike. Each Friday would see us on the 6.00pm train from Northorpe Station to Heckmondwike, fare three halfpence return. We would run up the steps to the baths, have a soapy shower, swim a few lengths and back on the train at 7.30. We became very good swimmers and still are, and swimming became a lifelong interest for me. As we got older we were allowed to go to the second house on Saturdays at the Pavilion Cinema at Ravensthorpe. We used to queue, pay our sixpence for a seat at the back then scoff a bar of chocolate (tuppence).With a supper of fish and chips (eight pence) eaten out of newspaper as we walked home.

Working Life

At the ripe old age of 14 I had to leave Crowlees School and find a job. It was obvious to me that I wanted to be an electrician but there wasn't much of a chance with just elementary schooling. My folks could not afford an indenture, so I had to look elsewhere and found a job as a piecener in a textile mill, Kilner Bros in Newgate. This entailed working in a mulegate and repairing ends as they broke and changing bobbins. We worked 7.00am to 12.00am with half an hour for breakfast and 12.45pm to 5.00pm, 5 Days and 7.00am to l1.45am, on Saturday morning. A 48 hour week and the pay for this most boring of jobs was just 10 shi1lings (50p).

I Lived on my Bike

In those days (1933-9) I really used to live every spare moment on my bike. In addition to using it to go to work, we used to set off for a day out on Sunday, riding at least 100 miles in the day, more if we went to the coast. On one of our trips we cycled down to Brighton taking eight days one way. On other holidays we toured the coasts of Norfolk and Suffolk. I got to know the Dales and Derbyshire like the back of my hand. In 1938 I acquired a tandem cycle, stripped it down to make it sportier and repainted it. Different friends rode on the back the last one being Arnie Hirst, a cheerful soul from Ravensthorpe. We were cycling through Keighley one time, I had my head down and I couldn't understand why pedestrians were laughing at us. Then I found that Arnie had his feet on the handlebars and I was doing all the work.

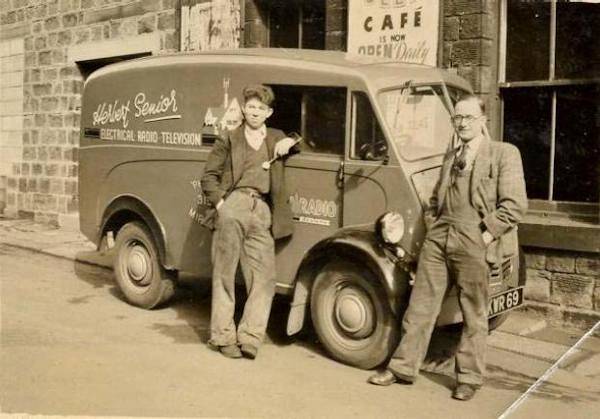

In due course I got my wish to get into the electrical trade thanks to my dad's brother, uncle Fred. He had been talking to local electrical engineer Herbert Senior and he mentioned me. Out of this came an interview, followed by the offer of a job. It meant going back to ten bob a week as I was now aged 15 and getting 13 shillings at Kilners. My mother wasn't very keen, because my wages made a lot of difference to the family income. She was persuaded however and I started as an apprentice with Herbert Senior in 1934. Some apprenticeship that turned out to be! My job was to look after the battery charging side of the business. Most radios had a "dry" high tension battery and a low tension "accumulator" which was rechargeable by passing a D.C. current through it for a few hours until it was fully charged, rather like a car battery. These accumulators were like a squat glass bottle containing lead plates and filled with sulphuric acid. My clothes were scruffy at best, but soon became rags with acid splashes. Sweeping up, running errands for the small staff and the old tyrant, the bosses wife, gardening, feeding the hens. "What's this got to do with being an electrician?" I used to wonder. Somehow I stuck it out because from time to time they sent me on a job with an electrician when they were stuck for a hand. The business was expanding as some of the local mills were being electrified, which meant that instead of a large steam engine, driving line shafts and the machines being driven from these by a flat belt, each machine was being fitted with its own electric motor. This meant a lot of fitting work and a lot of wiring to undertake. In addition lighting was being improved which meant more wiring and more and more houses were having electricity installed for the first time. After some ten months or so, Herbert set on another lad and I went with one of the men, working out on jobs. Because I was so keen, I learned quickly and after a couple of years was trusted to do wiring and other jobs on my own. These were usually house wiring and contracting was, and still is, very competitive. Labour was very cheap and, as this was before trade union activity; lads were allowed to be responsible for wiring jobs. We also did a bit of radio repairing and we used to rewind motors which had burnt out due to overloading. There were also domestic appliance repairs (fires, vacs, washing machines etc.) which nowadays are specialists' jobs.

The War Years

In 1938 warlike rumbles were coming from Germany. Prime Minister Chamberlain came back from meeting Adolf Hitler with his notorious "peace in our time" piece of paper. I didn't understand politics then, I just wanted to get on my bike but it soon became obvious, that politics would affect me, and very soon. The government were going to bring in conscription and I was the in right age group. In Mirfield we have a long tradition of volunteers and in 1939 the local territorial unit was 373 Company, Duke of Wellingtons Regiment, whose role was to defend the local area by locating enemy bombers with searchlights so they could be seen by anti-aircraft gunners, there being no radar in those days. It sounded to be just the thing for me, as I was going to be called up anyway, and I might even get into my own job. So, soon after my 20th birthday, I signed on for four years Territorial service and ended up doing six and a half regular service. In July we went off to camp at Pollington near Goole for four weeks training. We lived in tents and practised searchlight drill and square bashing (marching to order). We were allowed out into the village and to Goole, where we also used to go swimming. It was a wonderful summer and I must confess, I really enjoyed the experience. There was no holiday for us that year as Herbert Senior wasn't pleased when I joined the Territorials. He was even more annoyed when after being back at work for a little over a month the "balloon went up" and on the 28th of August (my mother's birthday) we were mobilised and had to report to the Drill Hall in Nettleton Road at midnight in full kit, although most of us were there long before that.

We slept very little that night on the Drill Hall floor and early next morning we were marched along Eastthorpe to the Coop Cafe at the bottom of Knowle Road, for breakfast. This cafe later became the R.A.F.A. club. We thought we were heroes, when, later in the day, as we went through Bradford on the train on the way to collect stores from Otley, old ladies shouted after us, with cries of "give him one for me lads". The hit tune at the time was "South of the Border" and we were singing this as we went to war. Our designated site was at Gildersome near Leeds and we got there late in the day and got cracking erecting tents. The searchlight equipment had to wait until the next day. Our detachment of ten men, one a sergeant, worked steadily at it and became temporarily operational by teatime. It was a tough time and the weather had changed for the worse. We should have been issued with greatcoats but they didn't have them in the stores, in fact we didn't get them until nearly Christmas. At that time were short of a lot of things, rifles were first war Lee Enfields and the main defence was an ancient Lewis gun. On Sunday 3rd Sept I was invited by some new friends, the Wales family, who lived across the road near the site, to listen to the radio at l1.00am, when the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, was to speak. He told us, and the world, that we were at war with Germany. We knew then we were for it, this wasn't camp, this was for real! That night we had the first air raid warning and all over Leeds searchlights lit up. It was a false alarm and after a while we were told to get to bed, all except the one on guard of course, and we always had a guard after that. After just a few weeks on site, where I was promoted to Lance Corporal, it was decided that they wanted me in the repair party. I had to go into Company HQ to work alongside the "Staff Mecs" all Staff Sergeants, only one of whom knew anything about electrics.

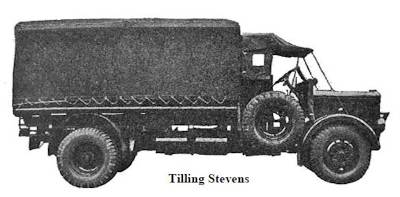

I had passed a civilian driving test in April so they allowed me to drive anything and this suited me fine as I liked driving. An army licence allowed me to drive motor bikes, cars and lorries even with a trailer on the towing hook. I drove a bus once and even a steam roller. We had to turn out in all weathers and had lots of adventures. On one occasion whilst driving a Tilling Stevens 19 lorry with a Lister generator trailer on the back, we were going downhill when I realised it was running away and the brakes were having little effect. The T.S.19 was specially made for searchlights and they had a powerful engine directly coupled to a DC generator. This was connected via a resistance control box and changeover switch to a DC motor that drove the rear wheels. This meant it could also power a searchlight whilst standing. The big disadvantage, which I had just discovered, was that there was no braking from the engine as you get on a normal vehicle. Fortunately the road was clear and I hung onto the steering wheel until we ran up the hill in front with no harm done, but a valuable lesson learned.

Within days of joining HQ we were moving, we had to go to East Yorks and the village of Patrington, where we set up our headquarters at Haverfield House The searchlight sites were scattered all around what is today North Humberside. Places with strange sounding names 1ike Thorngumbald, Hedon, Newlands, Sunkisland and Keyingham. The winter of 1940 was one of the coldest on record and some of our lads were living in tents. It's a good job we were young, daft and fit. The move to the coast was because the City of Hull was being plastered nightly by German bombers and we could see the fires 20 miles away. The inhabitants were having a terrible time and this was an example what happened to all our cities as the war went on. Our main job as Staff Mecs was to carry out repairs as necessary and we were called out to sites any time of the day or night. This meant travelling up to 40 miles usually in the blackout by utility car or on a motorcycle. Many times I got back from one of these trips at 2.00am only to be wakened at reveille at 6.30am.

Lance Corporal Highe

One horrible day of that winter I was asked to take a Bedford 3 ton lorry into Hull to the gas works for a load of ashes for spreading on the paths. I sorted out a couple of Pioneers (labourers) and we set off, but we never got there. On the twisting road, which was like a sheet of glass, I got into a skid and laid the vehicle gently on its side in the ditch. Luckily no one was hurt and we drained the water from the radiator as there was no antifreeze in those days, and went off to find a telephone. To my surprise the Commanding Officer, Major Lawrence, answered and his first question was "Is the vehicle alright?" before asking if we were safe. It took two breakdown trucks to get the lorry back on the road where it was found that the tyres were quite bald and no action was taken against me.

In the spring of 1940 we had to move again, to a new Militia camp at Pollington and until this was completed we had to occupy Cowick Hall east of Snaith for a few weeks. When we did move into Pollington Barracks, the army "bull" was pretty awful. In December, searchlight operations were transferred from Royal Engineers to Royal Artillery and for some reason that I'll never understand our Company became a Battery, Sappers became Gunners and Corporals, like me, became Bombardiers.

We had only one telephone line into the camp to a telephone in the orderly office and as it was a big camp, this made for all sorts of problems. I was asked if I could do something about it, so I went off to Goole to find a friendly GPO engineer and scrounge some plug jacks, cords, and indicators. With some help from the Battery joiner we put together a switchboard which, with some field telephones, did the job for nearly a year. Another unusual job I was able to do whilst at this camp was to install a fire alarm system to my own design. Because of the size of the camp and the danger of electricity supplies being cut off, it would have to be battery powered. I arranged for each of the barrack rooms to be fitted with a box containing a bell, batteries and a relay, the whole lot (about 20) linked together with a bare wire on insulators which ran round the camp terminating at the guard room with a control box which contained a 60 volt H.T battery, a push button and a switch. When the button was pushed the 60 volts was applied between the wire and earth and the relays closed, switching on the bel1s.The system worked well and it also acted as an air-raid warning and we left it behind, still serviceable, when we moved out. A further unusual job I got was to wire up an operations plotting table. Each of the sites under our Battery control was shown on a large map and we inserted a small bulb in a hole at the position of each site. When a searchlight was switched on the plotters switched on the relevant bulb and the controlling officer could see at a glance what was happening.

The soldiers on the sites had the worst time of all, ten men, one an N.C.O, living together in a hut. They were expected to be clean and tidy, perform guard duties, keep the rifles and machine gun and all the searchlight equipment in good order and be ready for instant action. I was glad to be on the repair party and enjoy the relative comforts of headquarters. We were at Pollington for just over two years and at times we felt as though we were being passed by as there was so much going on in the world. There were some compensations of course, because we had a big NAAFI canteen and a billiard room and some of us became good players. Also in the hall we could organise dances and shows, mainly from the talent within the unit and we were encouraged to do this to help keep up morale.

My ATS Girl

In 1942 we had a fresh intake of A.T.S girls straight from training units, some went into the cookhouse, some into stores and office jobs and the others became telephonist/plotters and it was one of these in whom I became interested, a tiny girl with a Geordie accent. Of course in any army there's always a lot of leg pull and you can't keep secrets. We were persuaded to go out together, so we had a walk down to the village pub. That was in 1942 and we have been going to the pub together ever since!

After the retreat at Dunkirk our unit like the rest of Anti-Aircraft Command, had to become "defenders on the ground" against an invasion. Everybody in the Battery was given a secondary job to train for; among these was the Mobile Platoon under the young second in command Captain Peter Goodall. He called in a Sergeant Danny Lee, a tough regular army man, from one of the sites, to train and toughen us up. Rough and tough he was too, as Peter Goodall found out as he trained us all, including the Captain, in unarmed combat. This change was a good thing for all of us, as we had become too static and bored with routine. It also made us feel involved and come what may, now we could defend ourselves. Thank God we never had to prove it!

One dark night we set out to test the defences of one of the sites out in the wilds, as we used to do in order to exercise the detachments. We would appear around 2.00am to find a sleepy guard who would raise the alarm and waken the rest of the lads. This time the guard was posted alright, but he was fast asleep. We captured him very quietly, complete with rifle, and took him back to HQ. The next morning when his Sergeant reported him missing, he was told what had happened and was told off. The poor Gunner was charged and given some CB (confined to barracks). The message soon got round the other sites and we never caught them out again. At this time we seemed to be getting instructions from all sides. I remember having to do a course on water treatment, how to purify and test it and then, as a secondary role, I was put in charge of the water supplies. Not a very exacting role in this country, but could have been if we were sent abroad.

There were also courses on new equipment as it came along. I attended training on new sound location equipment (still no radar) and auto remote control. Eventually, but much later in the war, we got Radio Location for Gun Laying which was early radar. Somebody once said that education is never lost and that stuck in my mind. I used to volunteer for anything in my line that came along. I had been given a lot of practical experience as an apprentice electrician but the theory was weak. Another reason for taking study courses was the upgrading which fol1owed and increases in pay. I found that, as a qualified Bombardier, I was better paid than a Sergeant. We were told to wear the Hammer and Tongs insignia on the right arm with the stripes to show that we were tradesmen.

Then we moved to Oakham in Rutland, from the largest county to the smallest, handing over the searchlight sites and Pollington Barracks to another unit. Just before we moved, we were watching the Wellington Bombers taking off from the nearby airfield when something went very wrong with one of them. The crew kept it flying until it cleared our camp, then, with the most horrible crump, it ploughed into the ground and caught fire. The bombs did not explode but the crew, all Canadians, were killed and were buried in the Churchyard at Pollington. We've been back to pay our respects since. At Oakham, we took over an existing HQ at Kimnall Stables, these were real stables and most of the other ranks actually had horse stalls for their barrack room. The A.T.S. girls were in Nissen huts across the road.

Again I was lucky as, together with a couple of other N.C.O.s, Martin Chambers and Harry Radford, was given a small room above the stalls. Spud Haley, one of our dispatch riders, was going to get married to a girl at home, so we put together a party in a pub up the road. We all managed to get a bit merry, but poor Harry who was a non-drinker, had too much and was drunk. Some of the sergeants, who should have known better, had found him and blacked his bottom with boot polish. In the early morning, Martin found Harry in a bad way under a cold shower, trying to wash it off. He was freezing so we put him to bed and later in the day, as he was obviously ill, we got the M.O. to look at him and he was sent straight to the nearest military hospital at the nearby airfield. Harry was suffering from alcoholic poisoning and was kept there a couple of days to recover and was put on a charge for being unfit for duty, I never heard about him drinking again. The Mobile Platoon activities carried on, manoeuvres, swimming rivers and running. We also used to organise sports days and football matches within the unit. I started running and playing winger at soccer and got quite good at both. Once I came in second in a race but I never had a first in any sport but despite this, I enjoyed it all.

The Happy Couple

The Happy CoupleIt was in the middle of the summer of 1943 when Nancy and I decided we would get married at the end of the year, around Christmas time. In the event I couldn't have leave then, so we had to settle for the 14th of December and be back on duty over the holiday. So at the little church at Greenside, near Crawcrook in County Durham, we were duly made man and wife. The first time I met Nancy's folks, I wondered what I was letting myself in for. Her mother had made me a pease pudding, quite the usual diet in Geordieland, but I had never had one before. They made me very welcome though. One day, I was sitting in the local club with Jim, her dad, surrounded by his pals who were all miners. They used to buy a round of drinks in turn but they wouldn't let me pay because of the uniform and I ended up with five glasses lined up and no way could I drink them. At the wedding we were accompanied by Nancy's sister Lorna, my sister Ethel, a small bridesmaid, Nancy's Mum and Dad and my Mother. For best man, I had managed to contact Arnie Hirst my old cycling mate and he travelled up in his Air Force uniform and slept the night on a billiard table in the Y.M.C.A. in Newcastle. After the wedding reception, Arnie went off back to his station at Dishforth and we went off to Berwick-on-Tweed for a short honeymoon. The train was delayed and it was late when we got to the small hotel. The landlady had saved our supper, which was dried up toad in the hole. There was a gas fire in our room and as it was very cold, we seemed to spend the entire holiday searching for sixpences for the meter in an attempt to stay warm. The army had funny ideas about married couples, you could stay in the same camp while you were courting, but as soon as you married, you were separated and so it was with us. Nancy was posted to another unit and from then on we had to meet whenever we could arrange to stay together, very unsatisfactory for a newly married couple. But, as we were always being told, there was a war on. We just had to make the best of it and grab a little happiness where we could.

The Harlequin exercise was designed to give High Command practice in deploying large numbers of troops in preparation for starting a Second Front in Europe. Also it was to test the air defences of the enemy over the channel. We in antiaircraft units, were to be the dummies. After leaving the huge amount of searchlight equipment we had acquired, we were issued with a scruffy collection of 15 cwt lorries which were fitted with machine guns. In these, we chased around the south coast and into Wales. The Welsh were not very welcoming and the only good thing I remember about that visit was Fellingfoel Ales. We also had a visit to the Isle of Wight and eventually finished up at Sandwich in Kent. The lorries were loaded onto landing craft which sailed towards the French coast, the idea being to encourage Gerry to bring out his fighters. We were a mock invasion force and our combined strength would shoot down the fighters. It's a good job they didn't take us on, as with the equipment we had, the whole unit would have been wiped out.

We saw very few enemy attacks after that and preparations for the Second Front went ahead at a fast pace. After all this excitement we found ourselves back on searchlights. This time we were at Woodhall Spa in Lincolnshire where we took over all the equipment from another unit. Nancy was with another Battery at Newark and we were still there when D Day came and went. In spite of several attempts to get into a more active unit, volunteering for anything that was going, I never got a chance to get overseas. Even when our Battery was changed to a Garrison Regiment, I didn't go.

Time on My Hands

I was told I was too useful as a tradesman and sent to the R.A. Depot at Woolwich. Discipline was very slack at the time I was at the Old Barracks at Woo1wich in early 1945. My new bosses gave me the job teaching young soldiers square bashing, I used to march them all over the district, just to pass the time. I saw the dental film "Your Teeth" more times than I care to remember when taking different squads to see it. Then, when my papers caught up, they realised I was a tradesman and found me a job in the dockyard. We three soldiers were working alongside civilians overhauling control panels. After a couple of days we were doing a panel a day just as they did, the only difference was they worked from 7.00am.to 5.00pm with an hour for lunch and we worked from 10.00am to 4.00pm and had two hours for lunch because we had a long walk to the depot. This was my first experience of a Trades Union working situation. There then followed a long nine weeks training course at Gopsal Hall in the Midlands. First I did a radio course and then radar. We were still there when VE Day came in 1945 and the war in Europe was over. Of course everybody went mad and even though we were on guard duty, we went down to the pub in the village. We got away with it because everybody was so happy. We thought that we would be going home but the National Government decided on a time and service device to decide when service personnel would be released. I was group 26 and didn't get released until February 1946. As usual I landed on my feet after the radar course by being posted me to the gun site at Wormwood Scrubs, behind the prison. Here I found there wasn't a lot to do. There was a good supply of R.E.M.E. Radar Mecs who didn't want to know about this Bombardier who, incidentally, had come out top in training and said he was a Radar Mechanic. Never being a scrounger I presented myself to the Sergeant Major and explained the situation and told him I was a tradesman electrician and driver, could he find me a job. Within the hour I was handed a rail pass and told to fetch a lorry from Mill Hill in North London. I didn't bargain for a left hand drive Dodge to drive through London.

I had plenty of time on my hands and took up joinery and we were taught how to use tools and make joints, this led on to making useful items for the home I was planning to set up. Nancy who had been discharged from the A.T.S when she became pregnant was getting together a "bottom drawer", and I was able to help. Mother's sister Ada lived at Hammersmith, not far from the Scrubbs and it was a handy port of call for me and I visited her and husband Jack Stockbridge and their daughter, my cousin Vera who was 18 at the time. I often took her to the baths at Chiswick as she was a very good swimmer. Jack loaned me his bike for getting around London which saved quite a bit of money in fares. Eventually he was persuaded to sell it to me and old Jack's cycle went home with me by train when I left the army. It became essential when I started work again. Uncle Jack hadn't had a holiday for most of the war years, and I offered to do his job for a week so that he could visit his relatives in Suffolk. He was a caretaker/night watchman which looked like an easy job. The idea was to sleep on a camp bed in the office of the emp1oyer, a joinery firm. Wakened by an alarm clock he had to go round the works every two hours where keys fixed to the walls had to be inserted into a clock which he carried to register the fact that he was doing a good job. A sleeping out pass was no problem and I did a conscientious job the first night, but the second night I found a better way to do it. By going round the keys and unscrewing them, than laying them out in order beside the camp bed and then, when the alarm went off, it was only necessary to turn the keys in the clock and get back to sleep, refixing the keys on the last round in the morning. When I told Uncle Jack he had a good laugh and called me a cheeky young b..., in all the years he had done the job, he had never thought of doing that. But he got his holiday and I could do my daytime job. After VJ Day, the end of the war with Japan, I was even less keen on the army as it seemed such a waste of time that I could have turned to useful effect. Rightly or wrongly, we had volunteered for four years and didn't expect to get out whilst the war continued, but we did expect to be released when it finished. We, the volunteers were first in, so should have been first out. In the six years, I had been changed from a carefree lad into a homeless married man with a very pregnant wife. A last, so called refresher, course at Formation College was enjoyable and I cheered up, I was good to be doing something useful again. We did some overhauling of motors, generator wiring jobs and repairs. The report at the end reads "Has a good knowledge of his subject, is also keen and is a very good practical man. Should pursue his studies at a Technical School". After this course, I went off to a holding unit at Crewe to pass the time to my release date on the 18th of February 1946. It was while I was here that I heard from my mother to the effect that she had been active on my behalf and had got the promise of a house to rent. Things were looking up, this was the best news of all, and it meant that Nancy and I could set up home together as soon as the baby was born. Because I had lived in the north my release had been arranged to happen at York. The day before with time to kill I made a note in my diary which I quote, "Sunshine, church parade and the Padre's explicit faith in the future for Christianity, the canteen, Jock and his bagpipes, Sunday papers, rubberised Yorkshire pudding and how I've come to hate army life. Plans for the future busy but rosy". Looking back at army life you tend to remember the good things and forget the bad. Things like the wonderful shows we got to see in the West End of London free of charge, playing football instead of just watching, going to dances, being fit enough to go for a three mile run before breakfast and enjoy it. We were lucky, my A.T.S. girl and I, we got through it, so very many didn't. It's probably worth recording at this stage, I was now 27, a testimonial on my release certificate reads like this, "Honest. sober, displays initiative and possesses ability and understands and knows how to organise men. Willing, loyal and hard working. Dated 15 Mar 46". Now that should get me a job anywhere, but what did I do? I took the easy option, I went back to Herbert Seniors.

Herbert Seniors 1950s

Herbert Seniors 1950s

Peace Time

We got the house to rent; it was a middle house in a block of four in Cyprus Crescent, out in the country between Northorpe and Dewsbury Moor. The property had been built just before the war as a speculation by a Dewsbury farmer. I had to start paying rent straight away and start cleaning it up as it wasn't very clean. Nancy couldn't help, being otherwise occupied having a baby and at this time staying with her parents in Geordieland, whilst I had temporary lodgings with my folks in a very crowded house/shop. Then I started work again at Seniors where the pay was a lot better than Army pay. During the war, electricians' pay had been increased from one shilling and nine pence an hour to two shillings and six pence (12.5p). Still we were desperately short of money. My post war credits and gratuity together only amounted to a total of £87. A useful sum but scandalous after six and a half years on low army pay. I was transferred to the Royal Artillery Reserve on 28 Feb 46 and then to R.E.M.E. in 1952. As I have heard nothing further I presume I'm still on the reserves.

Nancy's Mum with Brian at 14 Days

Brian was born on the 17th April 46 at Dilston Hall which is near Corbridge on the border of Northumberland and Durham. I had made a start at work, but took time off to be with my little love. When I was first shown Brian, within a few hours of his birth, he looked like an ugly, but familiar, old man. Needless to say by the time he was three months old, he was a much admired bonny child. After a year back in Mirfield we had got together some furniture and essentials and then the weather turned really bad. We had snow, snow and still more snow, it started in January 1947 and went on for a full eight weeks. Snow was eight feet deep and we ended up bringing coal on a sledge to try to keep a fire going and going to bed early to save fuel and keep warm. We couldn't take the lad out in a pram all this time, we just had to carry him and he was getting heavy at ten months. It was awful but then the snow went quickly and we had a wonderful summer.

When Peter was born in May 1950 we had Granny Gray staying with us to help. I borrowed my boss's big Morris Oxford to fetch him and Nancy home. Then decided to take Brian, now four and a good walker across the fields to Dewsbury Park. As we set off, Nancy called "Don't let him fall in the lake". An hour later, we were walking round the lake feeding the ducks when he let go of my hand and walked straight into the dirty water. I don't know who was most amazed, him or me. I fished him out, wrapped him in my raincoat and took him home on the bus to two very irate women.

We had been subjected to a lot of political propaganda during the war, some right wing but the bulk of it was left and main1y from the Labour Party. We also had lectures from the Liberals, Communists and others you never hear about now. I decided after a lot of discussions and arguments, when the elections came in 1945 I would vote for change and this meant voting Labour. This I did, along with a lot of other people and there was a "landslide" victory. I also decided to join a trade union which I did, as soon as possible after starting work. The Electrical Trades Union made me very welcome and I soon became a shop steward. It wasn't difficult, nobody else wanted the job. Eventually I became President of Dewsbury branch and held the office for several years. We were always demanding more money from the employers, the meetings were poorly attended and then something historic happened, vote rigging. The basic idea was to get Communists into office and delegations to conferences. It was not unusual to find nomination papers all filled in, with the same hand writing. Eventually it was sorted out by Brother Byrne, a national official, going to the High Court about it. The E.T.U. has been right wing in politics ever since that episode. The local Labour Party asked me to stand as candidate in the local elections of l948, something I was glad to do. My opponent was the Independent Jim Sykes. Over 30 years my senior, Jim, whom I knew very well as a friend of my dad, had loaned me his car to take my driving test in 1939. Needless to say I lost the election by about 60 votes. Jim became a very good councillor and is remembered by a small council estate, Sykes Avenue in Northorpe where my brother Donald lives. I left the Labour Party in the early 1960s over a particular and unfair tax and gave up union activities when I became a director of Seniors.

When it was suggested by Harry Phillips I should seek election to the local Coop committee I didn't know it was usual to wait for a vacancy. I just got hold of a ballot form, found some supporters and sent it to the secretary and I was elected. We used to meet in the big room upstairs, over the shop at Towngate. Most of the members at the time were railway men and I soon fitted in and enjoyed helping to run another business. As well as Towngate, we had a branch at Northorpe, one on Old Bank Road and the newly opened shop on Kitson Hill Road, our own bake house and coal distribution business. When I retired in 1984, we had closed the Towngate shop and stopped deliveries. All the shops had been converted to self-service and we had joined up with Heckmondwike Coop, a slightly larger society, but nothing like as successful. At the point of fusion, we had the all shops all, now they were at Grange Moor, Kirkheaton, O1d Bank Road, Kitson Hill Road, Northorpe, Nab Lane and Leeds Road, Dewsbury. We had a tremendous turnover and our profit in the last year as Mirfield Perseverance was £52,000 (£150,000 equivalent in 2012) all of this was applied to updating the Heckmondwike Coop shops. But sadly, it didn't work and soon after I had to retire at 65 there was another amalgamation. This time with the huge Yorkshire Coop. They closed the bakery, sold the shops at Northorpe and Grange Moor and partitioned off the shop at Old Bank to make lock up shops for letting to private traders, all very sad. However there are some happy memories of my involvement with the Coop movement during the long years of service.

I first went to the Mirfield Parish Church as a lad at Crowlees school, the then Vicar Tom Marsden, did his best to make we lads into good Christians. During the war I would enjoy most of the church parades but it was when our sons started Sunday School that we started going to evensong regularly. Only when I had got to 40 years old did Nancy and I get confirmed by the Bishop of Wakefield, Dr Tracey, famous for his interest in trains. We have been regular worshippers ever since. I also became a sidesman and in due course a member of the P.C.C. Eventually I became a member of the Standing Committee and Hall Manager for a year, then representative of the Church on the local Community Services Committee. In due time being elected to the chair of that committee. But that's not all, it was whilst I was chairman that a letter arrived for me (this was 1971) from the headmaster of the Secondary School at Kitson Hill. He was asking me to try and get the support of the people of Mirfield for the idea of purchasing Gearstones Lodge. So from being a member of the P.C.C. I had joined the Standing Committee, the Hall Management Committee, Mirfield Community Services Committee and soon, the Gearstones Lodge Committee.

In the early 60s, I sat on the Board of Governors of the Grammar School on behalf of the Labour Party. When I resigned from the party it also meant leaving the Board of Governors. The then chairman, Fred Brearly said he would like to see me back on the board. When a vacancy occurred they asked me if I would become a none political Foundation Governor and I was pleased to accept. With reorganisation of education in 1972/3 and after lots of meetings with education officials and Alec Clegg (later Sir Alec) of the West Riding County Council, we made the decision to go for comprehensive style education for Mirfield. It meant changing the Secondary Modern School at Kitson Hill and extending it, to make a new High School whilst the present premises at Castle Hall would become a Middle School. This meant the board of Governors would be surplus but Miss Nood, a solicitor who was a long standing member had other ideas. She said that we, the Foundation, owned most of the property and if Kirklees Council, the new education authority wanted it, they would have to pay for it. To our amazement the district valuer offered over £184,000 plus interest since the takeover, bringing it up to £199,000. In addition we were able to recover another £16,500 paid by Kirklees in tax. What to do with all this money? It didn't belong to us as individuals, except as trustees, so we set up the Mirfield Educational Trust and became a registered charity. The application of income from the money is directed to persons under 25 who are resident in the area of the old Mirfield Urban District Council to provide money, books, tools etc. to persons who need such help. The capital in the fund is well looked after by a London investment company and in spite of all the handouts over the last few years, the capital has now grown to over £500,000. It's very nice to give away money on such a scale and be able to help deserving youngsters. If only there had been something like this in my youth. We tend to spend heavily on the schools, because more people benefit, although we also help individuals. In addition we have been able to help with larger projects. Like the Sports Hall, made possible with our contribution of £150,000 over five years. We paid for repairs to Gearstones Lodge to the tune of £65,000, Scouts got £6,000 for canoes and camping equipment. We have spent a small fortune on computers, built playwalls, stocked up libraries, repaired a cricket pavilion, supplied microscopes, sent Scouts on a Jamboree in Australia, Guides to Thailand, as well as paying for courses for individuals in this country. In 1986 we spent £58,000, doing good works. When Fred Brearly died in the early 80s, I was appointed chairperson, a job I am happy to do.

Gearstones Lodge

Earlier I mentioned Gearstones Lodge. When Cecil Dorman wrote his letter to me as Chair of the M.C.S., suggesting that we buy the building, I put it to the members for discussion. It was decided to support the idea and to ask the Chairman of the Council, at the time Frank Lydall, if he would lend his good offices to raise the £5,000 needed. The money was to buy the property and leave £1,000 to put it in order. In the event, the public appeal, in spite of all our efforts, only raised £4,000. This was paid to the owner but there wasn't anything left to improve the building, which was in a bad state of repair. We formed a charity and appointed some locals as trustees and formed a management committee to run it. Gearstones Lodge quickly became a going concern, but without enough income to restore it to the standard we wanted. The lodge is in one of the wettest parts of Yorkshire, in the North Dales and damp problems became a constant worry. A lot of voluntary work went into it but it was a bit rough and ready. I visited several times but never slept there, understandably, the youngsters seemed to enjoy staying there and that's what mattered. Later when the Educational Trust was formed, I was able to persuade the members that perhaps we could do something about the lodge. I was delegated to go and discuss it with the Lodge management and I explained to them that we would be prepared to pay for a proper survey to be made and to finance some improvements. This was put in hand and the survey was carried out by a Leeds architect who also prepared an estimate to bring it up to Youth Hostel standard. This was would require £30,000 and we put the work in hand, but of course the estimate was exceeded and the Trust ended up paying out £65,220. So we asked for a mortgage arrangement to protect the Trust in the event the property was ever sold. From 1978 well into the 80s the lodge was used by over a thousand visitors a year. Then in 1985 the teachers decided to take industrial action and because they decided not to undertake voluntary duties, the High School stopped using the lodge. Others, Scouts, Guides and junior Schools continued to go, but it was no longer a financial proposition. At this time the Fire Service took an interest, but they wanted a lot of expensive alterations doing, the managers asked the Trust for further help, which in the circumstances, wasn't forthcoming. So the management decided to sell, but of course, as solicitor Richard Goodall pointed out, selling would not be easy. The trustees would have to be consulted, they would have to call a public meeting because the public of Mirfield were involved, the mortgage arrangement would have to be honoured. At the public meeting, the proposition was put "To ask the Charity Commissioners to allow people from further afield to use the lodge, thereby increasing its use and its income". That's where it rests in February 1988. Without the cooperation of the teachers I can see no future at all for this worthwhile project. My hope is that the teachers in due time will give a bit, before it is too late.